What Did I Just Agree To?

Are the terms of jurisdiction and dispute resolution enforceable?

Exhilirating.

Fascinating. Informative.

Binding. Ubiquitously, terms

which transfer most or all of the liability to the user are appearing at the

bottom of such pages. Responsibilities

are being surreptitiously imposed upon the “user” of the internet. To use a

term incorrectly, the “browser.”

Exhilirating.

Fascinating. Informative.

Binding. Ubiquitously, terms

which transfer most or all of the liability to the user are appearing at the

bottom of such pages. Responsibilities

are being surreptitiously imposed upon the “user” of the internet. To use a

term incorrectly, the “browser.”

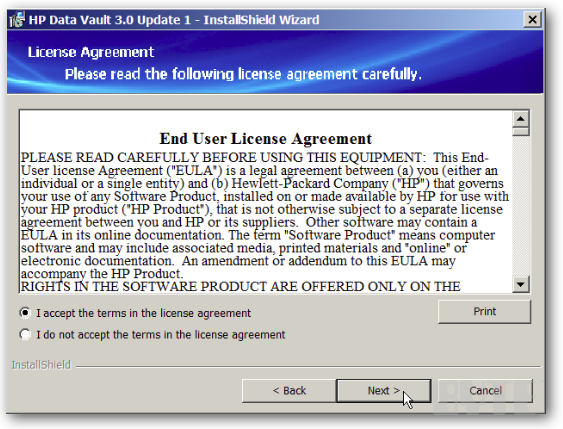

Large,

bulky, heavy and saturated with almost incomprehensible language, the consumer

is caught in a cross-sell whereby access to material is denied unless there is

agreement to these “terms”. A Quebec

court has looked into the matter.

Users can feel relieved that such tactics are not new. Principles of non-enforceability have been

examined before, and the principles of unconscionable practice as well as contracts of adhesion are not new to the courts either. What might be new is the

volume of such situations to be examined.

Micheal Geists’s article, “Quebec court says no to eBay’s online

contract”, (http://www.thestar.com/business/2013/03/29/quebec_court_says_no_to_ebays_online_contract_geist.html)

explores this issue in the matter of jurisdiction.

Selecting a jurisdiction may well be the easiest way to

ensure favorable treatment for the author, but it is also the most obvious

deceit for the courts to rule upon. If a

transaction goes sour, the easiest way to avoid the possibility of dispute is

to make the forum for dispute resolution inaccessible to the average website

user. Ebay’s principle offices are in

California, and their terms had it that the laws of the user’s location may

prevail, however any proceedings must take place in California. This makes things easy for a giant like Ebay, which has offices

all over the world but not so for the Quebec Students involved in a dispute with

the giant, as described in the article. A contract may be valid in

form, but this does not meant it can’t be rejected on other grounds.

The case involved an online auction, which was terminated by

Ebay prior to its conclusion. The

sellers sued Ebay in a Quebec court and argued jurisdiction since they were

located in Quebec. Ebay countered by

noting terms of use stated that all disputes are to take place in California. The court also noted that the clause was buried

deep within pages of dense material with conditions stacking one on top of the

other, so much so that the stipulations would require” very good eye sight and

lots of patience and determination,” to find

the provision stipulating California as the forum for disputes.

Jurisdiction itself is not new to contracts, many having a

clause that stipulates both parties have agreed on the laws to be utilized for

interpreting the contract and agreeing to the jurisdiction of dispute, but

mainly in the area of commercial contracts where it is presumed that all

clauses have been negotiated. In the

arena of the consumer contract, this is relatively new ground. This ruling runs counter to earlier cases,

where deference to freedom of contract was upheld.

The desire of parties, the electronic merchants and the

electronic consumer, to enter into commercial relations and the effectiveness

and efficiency of e-commerce weighed heavily on these earlier decisions. As the author notes, these were the concerns

of an Ontario court in 1999. The Quebec decision

”suggests that e-commerce is also dependant on fair contracts that grant a

genuine ability to pursue legal action in the event of a dispute.”